Writings & Photography

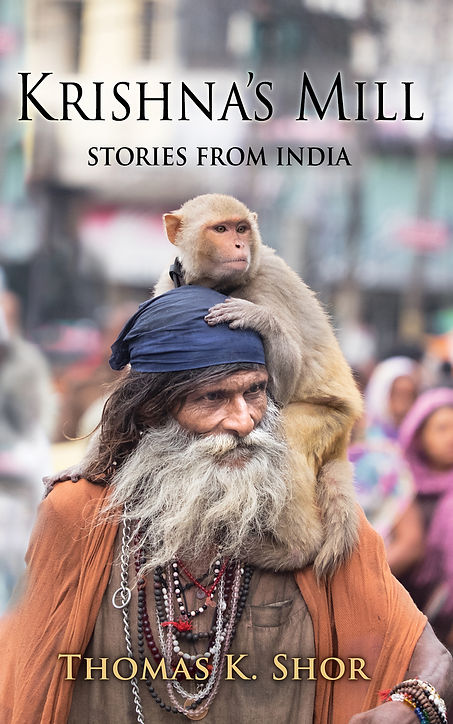

Krishna’s Mill

Stories from India

City Lion Press, 2022

Contents

Krishna’s Mill

Defender of the Dharma

The Interior of a Dot

Amram, Balancing on the Edge

The Tunnels of the Creator

In the Den of the Siberian Tiger

The Tower of Daramdin

Also by Thomas K. Shor

About the Author

The stories in this collection all depict real people and events except for The Tunnels of the Creator, which is a work of fiction.

ILLUSTRATED WITH 25 PHOTOGRAPHS

SHORT STORIES FROM INDIA

THE PEOPLE YOU MEET...

A yogi in his Himalayan retreat who was once a millionaire Bombay cloth manufacturer, forced to return to keep his sons from killing each other over the empire he left behind.

An American Buddhist, a “Defender of the Dharma,” who confesses having defended his life, with death, and knows the feeling of a knife going into human flesh.

A long-haired Indian artist and philosopher who sings ecstatically the poems of the English Romantics, reads Sanskrit and German philosophers in the original, and paints miniature paintings made entirely from tiny dots that are but two-dimensional slices of the world he sees within the ‘Interior of the Dot’.

AND THE PLACES YOU GO...

From the exclusive Breach Candy Club on Bombay’s Arabian Sea, to a zoo in Darjeeling where an ancient Siberian Tiger lays dying…and to a remote Himalayan village where it is said that in some dim antiquity the early inhabitants built their very own Tower of Babel made of clay pots, meant to reach Heaven.

Is there really a temple complex and mountain in South India said to be underlaid by a vast network of tunnels so old their existence is clothed in legend and through which an entire population was said to have disappeared?

Krishna's Mill

City Lion Press, 2022

138 Pages / 6" X 9" (15.24 X 22.86 cm)

Paperback ISBN: 9781957890937

eBook ISBN: 9781957890944

Available from Amazon, Barnes & Nobel, etc.,

and worldwide from your local bookstore

Read the Opening Pages of

The Interior of a Dot:

Not long ago I was in Dharamsala, the Indian hill station that serves as the Himalayan exile home of the Dalai Lama. My camera was slung under my open jacket, and I was practicing my particular method of photography, which entails my becoming invisible. While I don’t believe in literal invisibility—at least I haven’t achieved such yet—I have on occasion come close. I’ve stood in the middle of a busy Indian market and taken a portrait of someone at close range when something approaching magic occurs. Though the person passing in front of my lens was fully aware that he was being photographed at the moment the shutter clicked, and had even given his tacit approval, there was something in it, almost a magic, such that if someone were to have asked him a moment later if I’d taken his photo I’m certain he would have retained no conscious memory of it, the moment it had occurred in having passed without a trace.

When out on my photographic excursions I move slowly in a state of deep concentration, my shutter ready, my eyes ever vigilant, slowing time in order to capture that 250th of a second slice. It is a form of meditation in which the visual predominates over the other senses to an extraordinary degree; the ideal is to be awareness itself: eyes wide open. Occasionally I’ve come close.

The most interesting part of the market in which to photograph was a place where five roads come together in a great mix of people and cars, taxis, trucks, and busses. Pack horses also pass through this intersection, as do cows, dogs, donkeys, and humans of every description. Monks brush shoulders with Israeli Rastafarians. Sometimes there are even monkeys swinging from the wires overhead, making their way across the landscape.

Western Buddhist practitioners, Taiwanese sponsors, backpacking travelers, Indian tourists, monks, nuns, lamas, porters, businessmen, beggars, merchants, and—if the truth be known—the occasional Chinese spy, all have good reason to pass through this busy crossroads in the course of their day.

I had been there a while this particular afternoon when I noticed looking at me, from under a black felt hat and beneath bushy eyebrows, a long-haired Indian gentleman of questionable repute. He was clutching an artist’s satchel. I had half noticed him hovering in the background as I photographed, standing at a slight distance as if distracted by the busy passage of people, yet always close enough to give the impression he was observing me, as if trying to intuit my photographic method. He appeared like this a few too many times for it to be chance. There was something nervous about him, as if he lacked something he hoped to find on the street. I did not feel like mingling with him, and as many times as he drew close, I moved away.

He picked his moment to approach me. Without my being aware, he stood exactly out of my field of vision, behind my shoulder blades like a thief.

“How do you do,” he said. His accent was Indian, yet had something in it of the British upper crust.

I pretended not to hear. He then said something about memory, or that he remembered me, but since I didn’t turn I couldn’t be certain it was me he was addressing, or at least I could deny it, so I stepped away feigning interest in a sweet shop on the corner. He had held back so subtly that my eyes had never quite settled on him. Since I didn’t now want to turn and look, he remained a moving shadow.

Some time later this long-haired gentleman came up to me again. This time he appeared at a more friendly angle and was standing just beside me when I turned. This time I could hear what he was saying.

“If I should remember you,” he said, “how should I remember you?”

“Why should you remember me?” I asked, suspicious of what he wanted.

“Why is not the question. That is a seven-year-old boy’s question. They’re always asking, ‘Why, why, why…’ I’ve seen you, and now we’ve spoken—so certainly will I remember you. Therefore, the question is not why. I ask how. How should I remember you? As a photographer?—I’ve seen you with your camera; as a lover of humanity?—I’ve seen your eye. Or perhaps you are a musician?”

“I am not a musician,” I said.

“May I invite you to a cup of tea?”

“I just had one.”

“I am asking you to a cup of tea,” he said, becoming a little testy, “because I’d like to open a conversation.”

I didn’t fancy going with this stranger. With the sun not far from setting, the light was becoming interesting.

“How should I remember you?” I asked.

“My friend,” he said, his voice edged again with irritation, “that is why I want to invite you to tea.”

I said nothing. He continued: “I have my store of paintings in here,” he said, indicating the black case he was clutching. “I’ve brought them today because it is my friend’s 60th birthday and I want to show them to him.

“You’re a painter?” I asked.

“Yes, and I also write.”

“What do you write?”

“For four years now I’ve been writing a book; four years—or has it been eight?”

He laughed at the irony of his imprecise notion of time.

“The theme of the work is the spiritual in art. It was a question posed by the abstract impressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky. For this work I’ve had to read a lot—especially 19th and 20th century philosophers from the West, which I believe is your side of the world. I also know Sanskrit quite well and read in Eastern Philosophy—Hinduism, Vedanta, and the rest. The philosophers of the East can sometimes make your Western philosophers look like children, you know.

I also play the drum, and I sing English poetry. All the metaphysical poets. Almost everybody: Wordsworth, Shakespeare, William Blake.

It is because of my book that I have come here to Dharamsala—to have the silence of the mountains in which to write. Only when it is done, only then can I go to the market with my paintings.”

“You want to sell your paintings?”

“I want to bring them to the public’s attention—and to get my pound of gold, and my glory. But fame and fortune can never be our true aim. That is why our psychology calls them extrinsic motivations. If the artist is an artist—and this applies to the spiritual man as well—the motivation for his work must solely be intrinsic, coming from within.”